Over the past month, we have seen considerable outrage and excitement over the Internet Archive’s National Emergency Library, an online source of 1.4 million books that are free to borrow with no waiting list.

Chairman of the Senate Intellectual Property Subcommittee Thom Tillis (R-NC) sent a letter to Brewster Khale, founder of the Internet Archive (IA), expressing his concern that the National Emergency Library (NEL) is acting outside the boundaries of copyright law, noting that he is unaware “of any measure…that permits a user of copyrighted works to unilaterally create an emergency copyright act.”

Given the legal, economic, and societal implications of the NEL, it’s worth taking the time to address some of the criticisms of this project. In general, while the NEL’s legal status is unclear (even more so than the open library that came before it), it is a necessary balance against the closure of brick-and-mortar libraries around the country, with uncertain costs to artists and clear public health benefits.

What is the National Emergency Library?

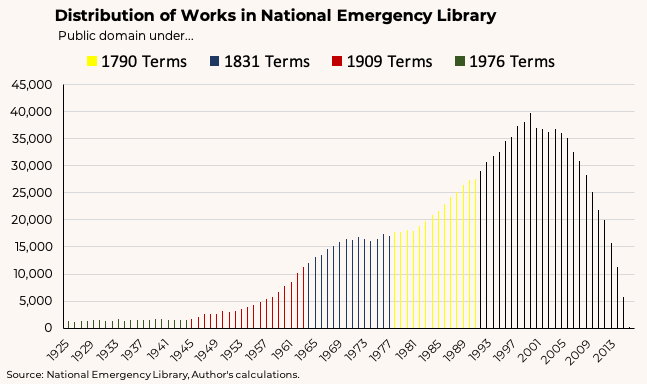

On March 24, Chris Freeland of the Internet Archive announced the creation of the National Emergency Library, an extension of their extensive 1.4 million-book Open Library.

Previously IA’s digital open library allowed users to “check out” books that were scanned one at a time. The change that the NEL brought about was the end to the waiting list, allowing anyone to borrow a book even if someone else has already borrowed it.

This move has generated considerable outrage in the rights holder community. In The New York Times, President of the Author’s Guild Douglas Preston offered scathing criticism of the the NEL:

Let us be clear: The National Emergency Library is not a library. It is a book-piracy website. Internet Archive has not paid a dime for these books, to either authors or publishers; instead, it acquires donations of used books from various sources. After scanning, it stores those books in warehouses, claiming that its ownership of the physical book gives it the legal right to lend out digital copies.

Legitimate libraries also lend e-books free, but there’s a huge difference: They pay expensive licensing fees for those e-books, and a portion of the fees flow to authors as royalties.

There are a few falsehoods and misleading claims that must be corrected. The article begins by expressing concerns for authors with new books coming out. It is undoubtedly true that the cancellation of book tours and physical copies sitting in warehouses and not on shelves harms those with new works, but none of this applies to the NEL. It does not hold books that aren’t at least five years old.

Authors may also request to remove books from the NEL, and while the Author’s Guild implies that rights holders must send a formal DMCA takedown request, NEL may be contacted directly by authors in many cases.

Of course, these misunderstandings about the National Emergency Library don’t change its legal status. And general concerns about support for authors merit closer examination.

Support for Authors

The strongest case against the NEL is that by providing books for free, it deprives rights holders (a group that includes publishers, not just authors) revenue they expected. This has been melodramatically equated with looting after a hurricane, but that just isn’t the case. The nonrivalrous nature of ideal objects makes it such that the consumption by one doesn’t prevent another from doing the same. This is a false equivalence, plain and simple, and those who use this analogy do not deserve the moral high ground they seek.

The category error in the treatment of ideal objects as property, however, does not invalidate the need for copyrights and patents. The potential for free-riding to deter investment in the production of creative works is real (though overstated), and requires some form of government intervention to address.

At the same time, not every act of infringement equates to a loss to the rights holder (who is in many cases not the author). If the goal of NEL’s critics is to protect the ability of artists to earn a livelihood, it is a noble one, but also does not require an unqualified condemnation of NEL.

Reading a book on the NEL doesn’t imply a one-to-one reduction in the purchase of another book. First, it may be the case that a book on the NEL is difficult to find in either a traditional library or anywhere else, as librarian and author Barbara Fister commented, making the choice not between “piracy” and purchase, but consumption or doing without. Second, just like a carjacker who steals a Rolls Royce he wouldn’t have otherwise bought, it cannot be assumed that the reader of an NEL book is denying the publisher any author revenue. As Fister explains:

I don’t think [critics of NEL] understand how unlikely it is that allowing multiple users of these versions of their books will adversely affect their income…Admittedly, like most authors I don’t depend on my writing for a living; perhaps if I did I would feel differently.

What’s more, the physical copies of books currently sitting on physical library shelves will stay there for the foreseeable future. These are books whose free access is perfectly legal but impossible now because of library closures. The NEL attempts to correct this temporary imbalance. According to the Internet Archive’s report on the first two weeks of borrowing, most of the books were only borrowed for 30 minutes and the total lending is comparable to that of a library in a town of 30,000.

To use economic jargon, consumption of ideal objects is strictly welfare-enhancing. For those whose reservation price (what they would be willing to pay) for a book is below the market price, borrowing from the NEL has no effect for the rights holder as they weren’t going to be paid either way. It is only consumers whose reservation price is above the market price that are “depriving” rights holders of anything.

Under conditions of *reasonable* enforcement, most media piracy does not represent lost sales. This is a simple result of the supply-demand curve. Many more people will download an e-book for free than will even pay $1 for it, let alone the $13 that traditional publishers charge!

— The Other Rick Wayne (@RickWayneWrites) March 31, 2020

While the number of consumers in the former category is likely going to expand dramatically due to the increase in unemployment, the announcement of the NEL includes this message to the latter category:

We recognize that authors and publishers are going to be impacted by this global pandemic as well. We encourage all readers who are in a position to buy books to do so, ideally while also supporting your local bookstore.

This appeal to those who can afford to purchase books provides a segue from any direct harms due to forgone revenue to broader concerns about authors’ ability to earn a living.

Despite the romantic vision of starving artists, poverty is anything but romantic. But producers of creative works deserve food, shelter, healthcare, etc. not due to their status as artists but due to their status as humans. Using copyright law as a load-bearing feature of the welfare state is seriously misguided, as Annemarie Bridy and Meredith Rose have pointed out:

If we want to help struggling artists, we need a strong social safety net for everyone, including universal healthcare and robust public funding for the arts and humanities. Copyright cannot carry all the weight of sustaining the arts.

— Annemarie Bridy (@AnnemarieBridy) April 22, 2020

There is no universe in which a person’s ability to feed themselves and their family should be predicated on whether or not their creative output is commercially viable at mass scale.

— Meredith Rose (@M_F_Rose) April 22, 2020

This isn’t to say by any means that support for robust copyright protection implies opposition to a broad-based welfare state, or that they’re mutually exclusive. And this argument is separate from the Demsetzian arguments about exclusivity in ideal objects encouraging productive use. But the point must be made: support of copyright as a tool to provide artists with a stream of income privileges artists above other struggling persons in discussions about poverty.

How to provide relief to those struggling economically during the current pandemic is a separate policy question entirely. But if artists were already struggling and consumers across the nation need to cut expenses on things like books, efforts to support authors are misspent attacking NEL.

A Balancing of Interests

I would expect the NEL, should copyright infringement be claimed, to have an uphill battle in court. Fair use, the use of protected material in a way that is not infringing, has helped Google Books and HathiTrust in the past. While previous victories for Google Books and HathiTrust are a good sign, but they are far more limited in their scope compared to NEL.

But if the law is indeed against IA and the NEL, then it is the law that must be scrutinized more closely. This is not the only aspect of copyright law that is coming under closer scrutiny during the COVID-19 epidemic: there are significant legal ambiguities surrounding distance learning, online religious services, and other uses of copyrighted material that would be perfectly fine in-person but in a legal grey area when transmitted via a Zoom meeting or streamed. Congress would do well to address these problems, not just for the sake of resolving ambiguity but to craft copyright policy that appropriately balances the interests of both authors and consumers.

The first-sale doctrine in the physical realm is justified, in part, by the fact that used copies have a competitive disadvantage relative to new ones. As Steven Tepp explains in his thorough legal analysis:

Opponents of [digital first sale doctrine] proposals point out that the relative perfection of digital copies, combined with the distribution facilitated by the internet, would produce substantially greater harm to the copyright owner than the existing first sale doctrine. A dog-eared, coffee-stained copy of a paper book competes with brand new copies only in a secondary market. Purchasers may choose that, knowing they are getting lower quality for a proportionately lower price. Digital copies are indistinguishable – “used” digital copies compete directly with the copyright owner in the primary market. Further, in the pre-digital world, transferring a copy involved identifying someone who wanted a copy of that work and physically conveying it to that person. Online auction sites and instantaneous transmission of digital copies make it easier to identify and deliver a copy to a person who wants it.

I would dispute that the selection offered by the NEL is identical to that of a traditional e-book. As scanned copies of physical books rather than an e-reader friendly file, they are the digital equivalent of a dog-eared, coffee stained used copy referenced above. This problematizes claims like Mary Rasenberger’s to the New York Times: “All they’ve done is scan a lot of books and put them on the internet, which makes them no different from any other piracy site,” she said. “If you can get anything that you want that’s on Internet Archive for free, why are you going to buy an e-book?”

But leaving that aside, this treatment under copyright law is at odds with how property rights are traditionally understood. One’s permission to sell a used toaster at a garage sale should not depend on whether or not it is of inferior quality to those sold at the store, and preventing someone from selling their toaster on eBay because it puts them on an even ground with every other online retailer would be laughable.

Would the creation of a digital first-sale doctrine “translate[] into substantially greater losses to the copyright owner”? It certainly reduces their profits, but this is a feature of a competitive market system. Whether or not the allowance of a robust digital first-sale doctrine would increase competition to the point that it undermines the incentives to create is another question, but these arguments only make sense if copyright is treated as a subsidy for creative works and not a traditional property right.

All of the arguments against NEL providing reading material for free are arguments against libraries themselves. As Brian Frye puts it, “libraries literally exist for the purpose of enabling people to consume information without paying for it.” If I donate a book to my local library that someone would have purchased, doesn’t this deprive the rights holder of revenue? What if a library purchases a book (or e-book license) and this turns into a net loss for the publisher based on the number of readers who would have otherwise paid?

In the context of the NEL and the internet, all of this must be qualified by stating that the potential for distribution is vastly greater and there is a substantive difference between NEL and your local library. At the same time, this difference makes the works that copyright law is designed to incentivize more widely available. These are all relevant considerations in crafting copyright law and judging NEL in general. Only if NEL leads to a measurable reduction in the output of creative works and such a reduction is not balanced by the gains from increased consumption can we say that it is a net harm to the creative ecosystem.

The same can be said for a broader digital first-sale doctrine, a policy Brink Lindsey and I support in our paper “Why Intellectual Property is a Misnomer.”

In closing, it’s relatively easy to flip the script on the narrative surrounding greed and selfishness. Though the NEL is a nonprofit institution, and thus doesn’t financially benefit from the NEL, publishers and authors do benefit from the purchase of their books. “The public must support authors and publishers by purchasing their books” can easily be turned around to “publishers and authors must support the public by offering their books for free.”

J.K. Rowling, who was at one point (on paper) richer than Queen Elizabeth II and is used an example of an author whose works have been found on the NEL, could certainly afford to give away the rights to her books, especially during this pandemic. (Though I could be mistaken, I only found one copy of The Sorcerer’s Stone in Italian in the NEL when searching for Harry Potter, along with a few other derivative works.)

Others, for sure, cannot. But why not implore authors who are more financially successful than most humans could ever imagine to be to make their works freely available? Why not encourage publishing houses to make their works available for free, and give (perhaps reduced) royalty payment to their authors? The latter would likely require some contract renegotiation, but the general point is the same: why are rights holders excluded from the appeals for benevolence and sacrifice being made to everyone else?

I have argued that in the face of depression-levels of unemployment and economic contraction, everyone should be chipping in, major rights holders included. This is no more radical a claim than arguing that those who are well off should give more to charity. In the case of the Open COVID pledge, many large private sector firms have joined in the effort to make their intellectual property freely available.

If all the NEL does is keep people inside and sane, it will be a gain for society that, based on the statistics available, would dwarf any loss of royalties to authors and publishers. Not to mention, it has opened a conversation on the state of digital lending. And testimonials from educators, researchers, and readers have shown that the NEL has accomplished the great good of making the pandemic a little more bearable. These considerations are not the only ones, but neither are those of the publishers railing against the National Emergency Library.

(+12 rating, 18 votes)

(+12 rating, 18 votes)